It was 100 years ago when the guns fell silent on the western front. 100 years later a small community in the rural village in Sussex are one of hundreds of communities pulling together to remember this historical milestone.

My band – Wadhurst Brass Band had a phenomenally busy weekend. We had a concert on Saturday evening followed by a church service, a rehearsal and then another concert on Sunday evening. All performances rather individual to each other. One particular moment of the weekend highlighted the entire meaning of the sacrifice that whole generation of Men laid their lives down for.

On Saturday night we played two twenty minute sets. The choir did a 20 minute set in the middle of our sets. I chose to keep the first set serious and relevant. It included “Hymn to the Fallen”, “In Flanders Fields” written by Gavin Somerset and Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance March No. 4. Our second set started with “Colonel Bogey”, followed by Karl Jenkins’ Lament from Stabat Mater. We finished our concert with a rousing performance of Peter Graham’s fifth movement from his “Cry of the Celts” – a very lively and meaty take on lord of the dance.

The acoustic of the church was immense. It’s as if it was made for a full 27 piece brass band. The band kept tight and true to the conductor and the performance clicked. Four notes call the piece to it’s end, before I had even turned around to the audience – two lovely ladies had risen to their feet, shortly followed by two more, then small pockets of people rose to their feet, and, before we knew it, the entire church was afoot with cheer and glee. The band had done it. Surely so, they deserved that standing ovation.

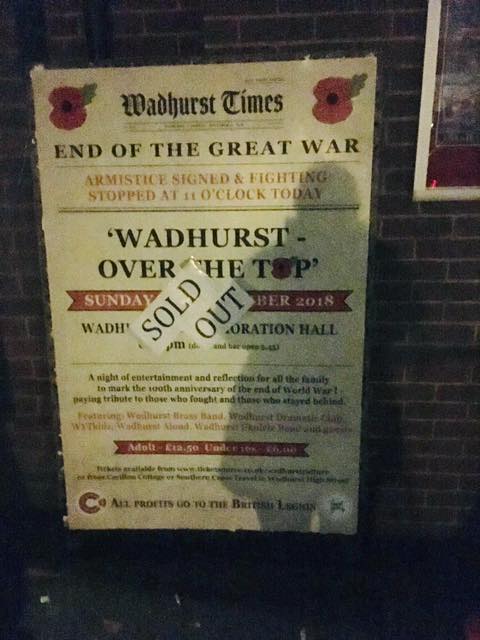

Then came Sunday. 100 years of celebration of armistice. We had a beautiful memorial service in the morning and it followed in the evening – when we participated in our biggest local project to date.

Wadhurst Over the Top, was a stirring concert that included members of both the Am Dram society and the children’s dramatics society. It included one of our local choirs “Wadhurst Aloud” and the Wadhurst Ukulele Group, as well as some singing acts. The concert started set in 1914 and ventured through the recruiting process, laughter behind the lines, loss and suffering and finally the victory and celebration. The bands two main contributions where to play “Aubers Ridge” which was a piece commissioned by the band – written by Stuart Fifield. It commemorates the battle of Aubers Ridge where most of our Wadhurst Men lost their lives. It was performed well and made a fitting tribute – but it wasn’t until the 2nd half where I experienced possibly the most poignant moment of my life in music to date.

2 hours later, the concert is approaching its grand finale. The war has ended and a young lad came in waving a news paper article simply reading “Peace at Last”. This was the point the Band finished the show with a hair-raising rendition of Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance No. 4.

I had my fantastic band directly in front of me, the entire cast of the concert on the stage perched above the band, The choir where stretched half way down the hall on both sides of the hall. We had just about got through the tricky bit at the start. The balance was perfect. The band, breaching the edge of their endurance, skillfully neglected to show a single sign of fatigue. I cued the band to start the molto rit in the coda before the final reprise of the theme of “Land of hope and Glory.” Each quaver perfectly elongated against the previous, the band followed flawlessly. As I looked round to make sure all 80 participants of the concert where ready – suddenly, it hit me.

If it was not for that generation of heroes, The silent generation , I would never have had the opportunity to stand in front of all these people 100 years later and conduct this powerful and nationalistic music. Never before had I ever felt so indebted to anyone in my life. With the pride in my heart I thought “this is for all of you guys who made the ultimate sacrifice” I turned to the audience beating time for all to see and I sung like I had never sung before. Something happened in that moment, I looked around to see all the smiling faces, joyfully singing with the cast, the band, the choir and I. The pure emotion was bursting through my face and everyone was in it together. I reiterate, This is only possible because of the sacrifices that those millions of men, women and animals made.

On behalf of every generation that has lived since that horrific time. Thank you brave warriors. Thank you that we can continue to have moments of incredible fellowship and fortitude. This whole experience taught me the true power of music – because, a village (somewhat) divided by political views and torn between traditionalism and economical development – even if for a brief moment of time, became one idealism. We were all there to celebrate, morn, laugh and cry. It’s thanks to music (and, of course, drama) – that each of us experienced all of these emotions together. It was raw, authentic emotion! and that, to me, is the power of the creative arts.